Introduction

Introduction

The introduction of a National Minimum Wage (NMW) law had, for many years, been central to NUPE’s argument for an effective trade union strategy to tackle low pay. In 1974, moving the union’s motion to the TUC’s Annual Congress in support a statutory national minimum wage, Alan Fisher, NUPE General Secretary, argued that the idea that legislation entailed a surrender of trade union autonomy was nonsense. Opposed by the General Council, it was defeated.

The core ideas, set out in ‘Low Pay and How to End It’ (1974) by Fisher and Dix were that (i) the scope, enforcement and effectiveness of the NMW depended on its connection to a broader bargaining and organizing strategy (in which, in NUPE, the path breaking work of Bob Fryer and his colleagues in the Warwick Report was crucial); (ii) the NMW as part of a legislative underpinning, including equal pay and fair wages, needed to be linked to a wider social and economic programme tackling poverty and inequality; (iii) it required reasoned argument, defining the low paid – overwhelmingly female, migrant and young – and the interaction of the NMW with other policies.

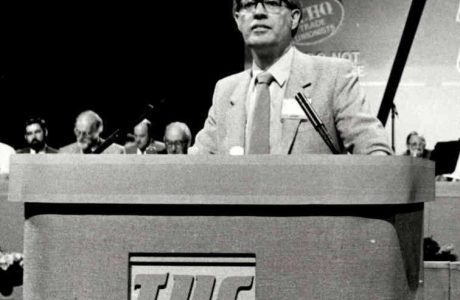

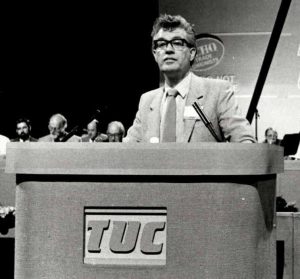

Rodney Bickerstaffe’s first speech to the TUC Annual Congress in 1982, following his appointment as General Secretary earlier in the year, was on the NMW. The consultation that followed, the first major review of trade union policy on low pay since 1970, lasted for four years by which time the case for more radical action had gained broader support.

Now so widely accepted it’s hard to remember how controversial the NMW was. Few economists or organisations, apart from staunch allies like the Civil Service Union and the Low Pay Unit and its Director, Chris Pond, supported it. Rodney stumped the country, speaking in half empty union halls and ill attended conferences. In 1983 he successfully moved a composite at the Labour Party Conference, calling for its introduction.

A Low Pay Forum involving other unions, academics and front bench Labour MPs was formed, making a significant contribution to shifting the argument within the Labour Party and the TUC.

In 1985, the motion moved by Rodney and seconded by Maggie Jones, NUPE Area Officer, attending as a constituency delegate from Putney, secured a two to one majority for the inclusion of a Statutory National Minimum Wage in Labour’s programme. In 1986 a similar motion at the TUC, although opposed by the TGWU and EETPU was overwhelmingly carried

Introduction & Shape of the NMW

By 1991 the policy on the NMW was in trouble: in the Commons Labour was getting hammered: every time the Shadow Employment Secretary attacked the scarily high unemployment figures, Michael Howard, the Tory minister, claimed a minimum wage would cost two million jobs; the Bank of England said it would increase inflation; support within the unions was beginning to fray with fears that it would be used to bring in an incomes policy and erode skilled craft workers’ differentials. John Smith, who had become Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer following Labour’s defeat in the 1987 general election, when there had been a palpable unease about advancing the economic case for a NMW set at two thirds of male median earnings, contacted Rodney. In Rodney’s words:

‘John Smith said ‘Rodney, you know I support the Statutory National Minimum Wage and we need to talk about the formula’ Can we try and adjust the two thirds as a medium term rather than an immediate objective? He said in the most supportive and friendly basis believing the Tories would try to rip us apart during the election period. John asked whether it might be possible for us to meet for a long evening to discuss the matter thoroughly on a private basis.

‘I then spoke to Peter Morris my senior research officer, and to Derek Robinson, senior fellow in economics at Magdalen College, Oxford’. (Derek a Barnsley man, son of a miner and a close friend of Rodney, whose refusal as Deputy Head of the Prices & Incomes Board to delay or modify the pay board’s report on miner’s pay led fairly directly to Heath’s defeat in the 1974 election had previously been economic adviser to Barbara Castle). ‘Derek said he would do his very best to fix something up. Within a day or two [he] got back to me and said…the President of the College had agreed to the meeting [and] that myself and John Smith and one other from each side would be welcome to stay in the President’s Lodgings overnight…’

‘I contacted John Smith’s office and it was agreed… we would arrive at Oxford, have dinner at High Table, and then begin discussions. I said that I would be bringing Peter Morris with me and John said that he would bring someone of whom I knew very little, Tony Blair, the Shadow Employment Secretary.’

John Smith argued that the formula was too high to be brought in in the first two or three years of a Labour Government. He wanted to keep a formula and put it to the electorate in the manifesto. There wouldn’t be an incomes policy because he didn’t believe the unions could deliver. Derek, who effectively chaired the meeting, kept saying ‘Rodney, you’ve never heard anything like this from a future Labour Government’. By around three in the morning – and two bottles of the Master’s finest whisky – an understanding was reached. ‘I would discuss the possibilities within…NUPE, and then with others, but that we could not guarantee anything. After many discussions…including, NUPE Research Officer, Virginnia Branney’s [role] in the Party’s Policy Review committees, all were agreed on a form of wording accepted by NUPE’s Executive…for a formula of 50% of male median earnings rising over time to two thirds.’

Soon after this Rodney wrote to Tony Blair as Shadow Employment Secretary suggesting it would be helpful to begin work on the legislative form of an NMW. John Cruddas, Policy Officer at Walworth Road, convened a small working group of lawyers, legal academics and union research/legal officers. The report, principally drafted by Bob Simpson, senior lecturer in the law department at the LSE, formed the legal basis for the National Minimum Wage Act 1988.

Low Pay Commission and the National Minimum Wage Act 1988

After John Smith’s death on 12 May 1994, the bargain struck first at Oxford and then in the various meetings between the trade unions and the Labour Party leadership was abandoned. The National Minimum Wage Act, skillfully nursed by Ian McCartney MP, became law in 1998, one of the earliest legislative acts of the Labour Government. A Low Pay Commission, chaired by Professor George Bain, drawn from employers, unions and academics, would recommend to the Secretary of State the level of the NMW.

The NMW was one of the undoubted successes of the Labour Government. Had John Smith lived it is probable it would have been introduced at a higher level, in a form more sympathetic to European ideas of social partnership, less individualistic in concept. As members of the original Low Pay Commission have subsequently accepted it was introduced at too low a level. Rodney’s view was that ‘what we got… is a Low Pay Commission, with good, intelligent and good-intentioned people, but who are not totally independent…The previously agreed level of a ‘Plimsoll line for labour‘, below which workers would not sink was replaced by a series of small pay rises from a very low beginning now challenged by many as being nowhere near the Living Wage that we had been envisaging for a hundred years.’

The NMW/Living Wage is planned to reach 60% of median earnings by 2020. The evidence suggests it is working but is not enough on its own to tackle the deep and messy problems the 21st century economy faces. There are problems, especially associated with the ‘gig economy’ and zero hours contracts, where higher hourly rates don’t help with unpredictable shifts or a fluctuating income; a ‘sticky floor’ where workers are trapped at the bottom; and the capacity of the Government, where only 90 inspectors from the Gangmaster & Labour Abuse Authority cover the whole of the UK, to enforce or tackle abuse. The case argued and fought for by Rodney Bickerstaffe and those before him for continuing effective action to tackle low pay remains.

Peter Morris